Drugs, divorce and incessant drum takes: Metallica on making metal’s biggest ever album

Now 30 years old, the Black Album has sold more than 30m copies. The band discuss its legacy, fighting in the studio – and making an all-star cover version

By the end of the 80s, it seemed certain that Metallica would be the biggest metal band in the world. Their 1988 album, … And Justice for All, had been in the US chart for a year and a half. Their first music video, One, had finally earned them MTV airplay, blasting their intricately crafted savagery through every TV set in the US. Their Damaged Justice tour had packed arenas across the US and Europe.

By the end of the 80s, it seemed certain that Metallica would be the biggest metal band in the world. Their 1988 album, … And Justice for All, had been in the US chart for a year and a half. Their first music video, One, had finally earned them MTV airplay, blasting their intricately crafted savagery through every TV set in the US. Their Damaged Justice tour had packed arenas across the US and Europe.

They seized their moment with the Black Album, as their self-titled next LP became known. Released 30 years ago this month, no metal album since has matched its impact; every parameter was reset for what such belligerent music could achieve. It went 16 times platinum in the US and has spent 622 weeks (and counting) in the US album chart. Its third single, the swelling Nothing Else Matters, passed 1bn YouTube views last month. The band are commemorating the record’s 30th anniversary by releasing a 52-track covers album, The Metallica Blacklist, with stars as giant and eclectic as Miley Cyrus, Elton John, Phoebe Bridgers and Biffy Clyro giving their takes on the album’s tracks.

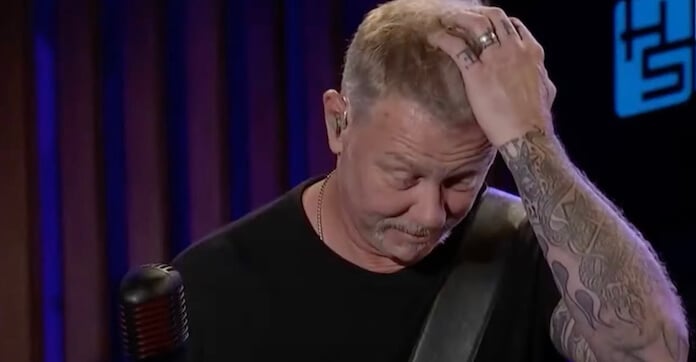

“Thirty years of the Black Album, it’s a pretty big year,” says Metallica’s singer, guitarist and co-founder, James Hetfield, rather drily – by his own admission, they are a band not usually given to looking back. “We’re overachievers and we’re perfectionists. We think outside the box and we try to be the first at things. There’s no nostalgia driving this band; we used to be very fearful of it.”

True to that spirit, Metallica defined a new subgenre – thrash metal – with their 1983 debut album, Kill ’Em All. The searing sound of hard rock virtuosity grinding with punk, it was a counterattack against hair metal’s domination of the scene. The next year’s follow-up, Ride the Lightning, controversially introduced acoustic guitars and bass solos, before 1986’s Master of Puppets became an underground smash, incorporating never-before-heard song structures and eight-minute-long instrumentals.

The subsequent Justice was an even bolder test of metal’s limits. For up to 10 minutes apiece, its monolithic tracks marched between countless time signatures. “The band’s breakneck tempos and staggering chops would impress even the most elitist jazz-fusion aficionado,” wrote the Rolling Stone critic Michael Azerrad in his review.

“There was a lot of ego and showing off on Justice,” says Hetfield. “Going out and playing Justice live, the songs were eight, nine, 10 minutes long.” The Black Album was the polar opposite. The previous albums had vibrant, politicised paintings on their covers; this one was jet black, broken only by an embossed image of a snake, while the songs were stripped-back rockers. No 10-minute suites, no wacky rhythms – just stomping, catchy, heavy metal.

Now 30 years old, the Black Album has sold more than 30m copies. The band discuss its legacy, fighting in the studio – and making an all-star cover versio

By the end of the 80s, it seemed certain that Metallica would be the biggest metal band in the world. Their 1988 album, … And Justice for All, had been in the US chart for a year and a half. Their first music video, One, had finally earned them MTV airplay, blasting their intricately crafted savagery through every TV set in the US. Their Damaged Justice tour had packed arenas across the US and Europe.

They seized their moment with the Black Album, as their self-titled next LP became known. Released 30 years ago this month, no metal album since has matched its impact; every parameter was reset for what such belligerent music could achieve. It went 16 times platinum in the US and has spent 622 weeks (and counting) in the US album chart. Its third single, the swelling Nothing Else Matters, passed 1bn YouTube views last month. The band are commemorating the record’s 30th anniversary by releasing a 52-track covers album, The Metallica Blacklist, with stars as giant and eclectic as Miley Cyrus, Elton John, Phoebe Bridgers and Biffy Clyro giving their takes on the album’s tracks.

“Thirty years of the Black Album, it’s a pretty big year,” says Metallica’s singer, guitarist and co-founder, James Hetfield, rather drily – by his own admission, they are a band not usually given to looking back. “We’re overachievers and we’re perfectionists. We think outside the box and we try to be the first at things. There’s no nostalgia driving this band; we used to be very fearful.

True to that spirit, Metallica defined a new subgenre – thrash metal – with their 1983 debut album, Kill ’Em All. The searing sound of hard rock virtuosity grinding with punk, it was a counterattack against hair metal’s domination of the scene. The next year’s follow-up, Ride the Lightning, controversially introduced acoustic guitars and bass solos, before 1986’s Master of Puppets became an underground smash, incorporating never-before-heard song structures and eight-minute-long instrumentals.

The subsequent Justice was an even bolder test of metal’s limits. For up to 10 minutes apiece, its monolithic tracks marched between countless time signatures. “The band’s breakneck tempos and staggering chops would impress even the most elitist jazz-fusion aficionado,” wrote the Rolling Stone critic Michael Azerrad in his review.

“There was a lot of ego and showing off on Justice,” says Hetfield. “Going out and playing Justice live, the songs were eight, nine, 10 minutes long.” The Black Album was the polar opposite. The previous albums had vibrant, politicised paintings on their covers; this one was jet black, broken only by an embossed image of a snake, while the songs were stripped-back rockers. No 10-minute suites, no wacky rhythms – just stomping, catchy, heavy metal.

This music became so prominent in global pop culture that Tomi Owó, the Nigerian R&B singer whose rendition of Through the Never appears on The Metallica Blacklist, remembers “seeing Metallica without even listening to the music. When I was in high school, my friends would come back from their summer holidays with Metallica shirts.”

“It was an amazing time that could never happen again,” summarises Jason Newsted, the band’s bassist from 1986 to 2001 (he was replaced by Robert Trujillo). “Demographically, the way the world lined up – the amount of people that were 12 to 22 years old, before the internet – it was such an important movement in time. We played 50 countries and they were all the same, as far as the togetherness and commitment to being a part of something so much bigger than you.”

For Hetfield and Kirk Hammett, Metallica’s lead guitarist, the first aim when writing the Black Album was to sprint as far away as possible from Justice’s incessant technicality. “One of the things that we all agreed upon was simpler, bouncier riffs,” remembers Hammett. For Lars Ulrich, the drummer, the reinvention meshed perfectly with his mission to invade as many ears as possible. “I’ve heard a story about them going to a strip club,” says Ben Thatcher, the drummer in Royal Blood. The garage rockers cover Sad But True on The Metallica Blacklist and Thatcher has long been friends with Ulrich. “A Mötley Crüe song came on and Lars went: ‘Man, why doesn’t a Metallica song come on when we’re in these places?!’”

Hammett corroborates: “That’s true, but there’s more to that conversation, too. He’d always think: ‘Those drums sound really good!’”

Already exhausted by their involuted songs, Metallica had jammed the riff of Sad But True – the Black Album’s slowest, heaviest cut – on the Damaged Justice tour. However, songwriting didn’t start properly until they got home in late 1989; much free time on the road had been occupied by what Newsted euphemistically calls “powders”.