The Summer of Stage Collapses

THE BUSINESS: The recent rash of concert catastrophes is prompting lawsuits and calls for increased regulation.

Coutless music enthusiasts have heard the tale of Van Halen and the brown M&Ms — how the ’80s mega-band insisted every one of the chocolate-colored confections be removed from its dressing room. What most might not know, however, is the reason, which had nothing to do with ego and everything to do with concert safety.

The way singer David Lee Roth explained it, the arena rockers’ technical rider was so detailed — like a “Chinese Yellow Pages” — that they purposely buried the candy request just before Article 148 specifying the weight (5,600 pounds) each of 15 sockets was expected to carry while hanging 30 feet above the stage. “If I saw a brown M&M in that bowl … well, line-check the entire production. Guaranteed you’re going to arrive at a technical error,” Roth said in 1998. “They didn’t read the contract. It could destroy the whole show or literally be life-threatening.”

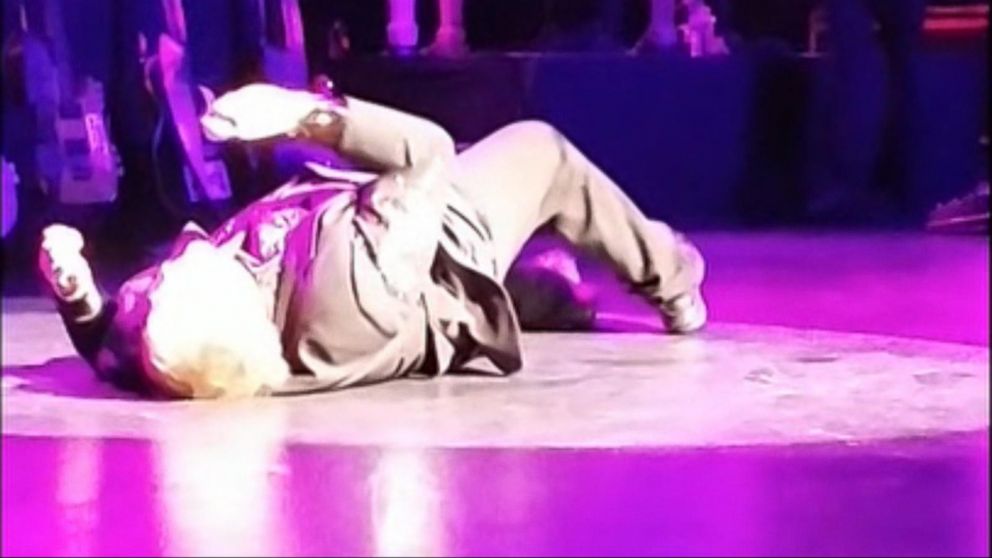

With the four weather-related stage collapses during a relatively robust summer concert season — on July 17 at Ottawa Bluesfest during Cheap Trick’s set; on Aug. 6 at the Brady District Block Party in Tulsa, Okla., just before the Flaming Lips were due to play; on Aug. 13 at the Indiana State Fair in Indianapolis, where a headlining gig by Sugarland was superseded by a windstorm that toppled a 50-foot-tall structure, killing seven and injuring 40; and on Aug. 18 at Belgium’s Pukkelpop festival, which featured more than 200 acts headlined by Foo Fighters and Eminem and resulted in five deaths — it’s a lesson event organizers, promoters, artists and crew might want to heed.

“I don’t know if it’s the stages or Mother Nature is just pissed at rock ‘n’ roll, but it’s a legitimate concern,” says Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl, who 10 days before Pukkelpop had headlined Chicago’s Lollapalooza in torrential rain. “Had the other shit happened before that, I would have been gone!”

Says one high-ranking concert industry executive: “Indiana was a fluke; it’s an accident you can’t prepare for. But I think it will lead to more stringent guidelines for wind tolerances, weight, roofs. … The industry will have to recalibrate how we deal with this.”

Indeed, by most eyewitness accounts, the 60 mph gusts that swept up the tented roof of the Sugarland stage came out of nowhere. But attorney Ken Allen, who is representing the families of three victims of the collapse in lawsuits, contends that fair organizers had ample opportunity to inform and protect attendees. “There were three warnings by the National Weather Service of severe thunderstorms approaching the area,” he says. “The lightning should be enough to postpone the event, but those in charge did nothing. Rather, at 8:39 p.m., [the crowd] was assured that a little rain was nothing to worry about and it would just blow over. Well, it didn’t.”

The suit, one of nearly a dozen filed so far (several demanding punitive damages in the tens of millions), lists as defendants promoter Lucas Entertainment Group, security company ESG, stage builders Mid-America Sound Corp. and Live Nation, whose reps would not comment to THR other than to “express sympathy for those involved.” In another filing, the state of Indiana is also named.

But making a weather judgment call can be complicated. If a band isn’t allowed to play, it could forfeit its pay. If the promoter pulls the plug, the insurance company can take issue with a claim. Unionized stage hands charge overtime for a delay, and, of course, there are the fans who paid for tickets. Foo Fighters tour manager Gus Brandt says the murky process of weather prediction is “kind of like Mom and Dad talking to the kids about sex. I’ll get with the promoter and our production manager, and we’ll agree in increments. Like, ‘If it gets this bad, we’ll do this.’ ”